Last Updated: 26 Mar 2025

Table of Contents

Introduction

In this article, I add upon Part 2 of the Outlier Detection Algorithm Series by exploring the various methods aimed towards accurately detecting cellwise outliers within a given dataset. We detail how each algorithm works, starting with a more expanded description of how our newly developed method Marginalized Mahalanobis (or MaMa). We then review the accuracy of each method in classifying cellwise outliers. We will see how MaMa is able to handle various scenarios outside of the multivariate normal distribution that the other algorithms struggle to handle.

Methods

In this section, I introduce our method MaMa, followed by five additional methods that have been developed within the last few years.

Marginalized Mahalanobis

Marginalized Mahalanobis (MaMa) is a method recently theorized by my advisor William Christensen and I developed in R programming. The steps involved is as follows:

We start by calculating the squared Mahalanobis distance for every row in $\textbf{X}$ to get $D^2$:

\[\begin{equation} D^2 = (\boldsymbol x - \boldsymbol\mu)^T \boldsymbol\Sigma^{-1} (\boldsymbol x - \boldsymbol\mu) \end{equation}\]The Mahalanobis distance formula computes the distance between observations within the data and the mean $\boldsymbol\mu$, also taking into account the correlation structure of the dat $\Sigma$. The significance of incorporating $\Sigma$ is to account for extreme values consistent with trends in the data to have a lower $D^2$ than any extreme values that are clearly separated from those trends.

For every column/variable $j$ in $\textbf{X}$.

- Compute the Mahalanobis distance excluding $x_j$, $\mu_j$, and $\Sigma_{j}$ to get $D_{-j}^2$:

- Compute the Marginalized Mahalanobis:

-

$W^2$ follows a $\chi_1^2$-distribution (when X is MVN).

-

If for each observation $i$ in column $j$,

where $\alpha$ is the selected significance level for cellwise contamination detection, then cell $x_{ij}$ is classified as an outlier.

The intuition stems from the difference calculation. If removing variable $j$ causes $D_{-j}^2$ to shrink significantly from $D^2$, then $W_i^2$ becomes large and is significant under the $\chi^2_1$ distribution. The algorithm will produce a matrix of binary indicators (TRUE/FALSE) suggesting which cells are anomalous.

Fast DDC

Fast DDC (Detect Deviating Cells) is an algorithm developed by Peter J. Rousseeuw and Wannes Van Den Bossche in 2017. Fast DDC works by first standardizing the data using robust estimates of the mean ($\mu$) and covariance matrix ($\Sigma$). It computes robust z-scores based on these estimates, and cells are flagged when their z-score exceeds a critical value from a $\chi_1^2$ distribution.

Flagged cells are temporarily removed, and pairwise correlations ($\rho$) are re-estimated using the remaining data. Fast DDC then imputes flagged cells with a best-case prediction value based on these updated correlations. If the deviation from the predicted value remains large, the cell is marked as an outlier.

The main advantage of Fast DDC is its computational efficiency, making it suitable for large datasets. However, its accuracy depends on the assumption that the data is approximately multivariate normal, which limits its application to non-Gaussian data.

Cell MCD

Cell MCD (Cellwise Minimum Covariance Determinant) builds upon the Fast DDC framework but introduces additional complexity to improve robustness and accuracy. Developed by Peter J. Rousseeuw and Jakob Raymaekers in 2024, it estimates the mean and covariance matrix using the Minimum Covariance Determinant (MCD) approach, which minimizes the determinant of the covariance matrix over a subset of the data.

Cell MCD computes the Mahalanobis distance for each point, then iterates through Concentration, Expectation, and Maximization (CEM steps) to refine the estimates of the mean and covariance matrix. This iterative process improves accuracy in identifying outliers, especially in small or noisy datasets.

Cell MCD is highly accurate and also effective for imputing deviating cells. However, its greater computational complexity makes it less efficient than Fast DDC.

DI

DI (Detection-Imputation) follows a two-step framework involving detection and imputation. Developed by Peter J. Rousseuw and Jakob Raymaekers in 2020, DI first computes robust estimates of the mean and covariance matrix.

-

In the Detection (D) step, DI applies methods like LASSO regression to identify cellwise outliers row-by-row.

-

In the Imputation (I) step, DI attempts to replace flagged values with best-case predictions based on the current estimates.

This process repeats until convergence or until changes in the covariance structure become negligible.

DI is effective for detecting and imputing outliers under the assumption of multivariate normality. However, it is computationally more expensive than Fast DDC and Cell MCD due to the iterative imputation step.

Cell GMM

Cell GMM (Gaussian Mixture Model) was developed by Zacharria et. al. in 2025. Unlike the previous methods, Cell GMM is specifically designed for data with a clustered structure, where different subgroups of data may follow distinct multivariate normal distributions.

Cell GMM works similarly to Cell MCD but introduces a modified C-step to classify which rows belong to which cluster. It estimates the mean and covariance matrix for each cluster, then computes the Mahalanobis distance within each cluster to detect outliers.

Cell GMM is highly effective for detecting and imputing outliers in heterogeneous data. However, it has significant drawbacks:

-

It requires tuning over ten hyperparameters for proper initialization.

-

It is computationally expensive due to the complexity of fitting multiple mixture components and refining cluster assignments.

As a result, Cell GMM is often impractical for large datasets despite its strong performance.

Simulation

Metrics

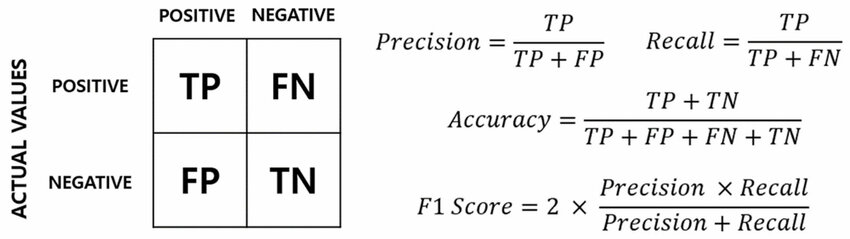

To test the efficacy of each algorithm in detecting cellwise outliers, we incorporate a Monte Carlo simulation framework in order to assess both the center and spread of the algorithm metrics. We treat successful detectors similarly to how classification models are assessed under a classification framework. The metrics we will focus on for our analysis are the following:

-

Accuracy: Simply put, the proportion we correctly predict as inliers and correctly predict as outliers.

-

F1 Score: The “harmonic” mean of recall and precision. In other words, it is the average of the proportion of correctly predicted outliers out of all true outliers (recall) and the proportion of true outliers out of all predicted outliers (precision).

-

Computation Time: The length of time to run the algorithm.

This figure below illustrates what is normally called a confusion matrix, which illustrates how accuracy and F1 score are computed under classification problems. Note the relationship between F1 Score and accuracy. While they are not exactly the same, they are closely related. For a low rate of outliers within a dataset (which is most likely in real-world situations), the accuracy can still be really high even if predictions on every cell is an inlier. F1 Score, ultimately, is a more indicative classifier when a model can find the outliers amid a sea of inliers. F1 Score mediates in finding all the outliers without over-classifying them (high recall, low precision), nor playing it safe by not classifying very few outliers (high precision, low recall). Thus, we utilize F1 Score as a secondary and powerfully demonstrative metric in determining algorithm success.

Distributions and Parameters

In order to simulate the different forms data could take, we simulated from the following distributions in our Monte Carlo simulation study:

MVN (Multivariate Noraml):

\[\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{X}_{n\times d} \sim N_{d}(\boldsymbol{\mu}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) \end{equation}\]$\mu$ is a vector of $d$ means and $\Sigma$ is a $d \times d$ covariance matrix.

Bimodal MVN:

\[\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{X}_{n \times d} \sim \begin{cases} N_d(\boldsymbol\mu_1, \boldsymbol\Sigma_1), & \text{with probability } p \\ N_d(\boldsymbol\mu_2, \boldsymbol\Sigma_2), & \text{with probability } (1 - p) \end{cases} \end{equation}\]This is essentially two MVN clusters within a dataset.

Log MVN:

\[\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{X}_{n\times d} \sim Lognormal_{d}(\boldsymbol{\mu}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) \end{equation}\]We initialize the creation of each distribution with a vector of $d$ means $\mu$, a standard deviation $\sigma$. We can also specify the means and variances for each cluster in a bimodal MVN dataset.

Covariance Structures

The form of the covariance matrix can also alternate between three types:

- Rho ($\rho$): The Rho structure assumes a constant correlation value $\rho$ between all variables. $\rho$ can be any value in $(-1,1)$. The covariance matrix for this structure is defined below as

- A09: Titled by Jakob Raymaekers & Peter J. Rousseeuw, this covariance structure is calculated to have stronger correlations among columns closer together, and weaker correlations for columns farther away.

- ALYZ: ALYZ variances are randomly generated correlation matrices following the procedure of Agostinelli et al. (2015) and typically have mostly small absolute correlations. The main point to illustrate with this type of structure is its wide variety to implement strong to weak correlations it generates in column data.

Outlier Settings

After we create our dataset from one of the three distributions, we then impose a proportion of the cells (called “rate”) to become one of the three types of outliers:

-

Type A: a cell value is much larger or smaller than expected. We define $z$ as the number of standard deviations ($\text{SD}(X_i)$) that $X_{ij}$ deviates from the true value.

-

Type B: a cell value is exchanged with a value found within the range of $\sim U[\min(X_i), \max(X_i)]$, imposed to exceed the 99th percentile of the Mahalanobis distance of the uncontaminated data.

-

Type C: A cell value is replaced by a specific value. This is based on the function

generateDatain thecellWisepackage (Raymaekers and Rousseeuw, 2022).

For more information on the outlier types, you can refer to Part 2.

Next Steps

In the next post Part 4, we will explore the results of each algorithm compared to MaMa under various combinations of the simulation parameters.