Last Updated: 29 Dec 2025

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What Goes in a Chord

- Data Source and Cleaning

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Methods

- Results

- Conclusion

Introduction

Music is the art of organizing sound through melody, rhythm, harmony, and timbre to create structure, emotion, and meaning. Most Western music follows a tonal system, which is a shared set of rules that governs how pitches relate, how tension and resolution emerge, and how musical ideas evolve over time. At the heart of this system are chords: collections of notes built from specific intervals that form the harmonic foundation of melodies and chord progressions. While trained musicians can often identify chord qualities by ear, distinguishing between dozens of triadic variants across keys, inversions, and pitch ranges is a challenging task. This project explores whether a deep learning model can learn to identify key chord characteristics, including tonality (major or minor), key signature, and inversion, using audio-derived harmonic features. By applying neural networks to this fundamental rule system of tonal music, the project sits at the intersection of music theory, signal processing, and machine learning, with potential applications in chord transcription, music analysis, and creative audio tools.

What Goes in a Chord

For this project, we only focus on detecting three-note chords. The components of a chord are as follows:

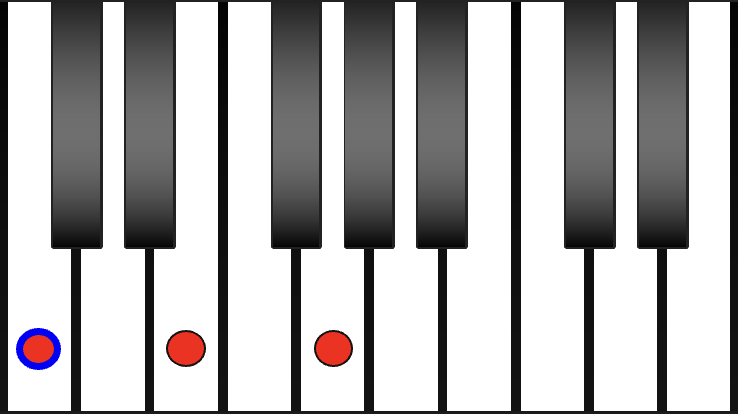

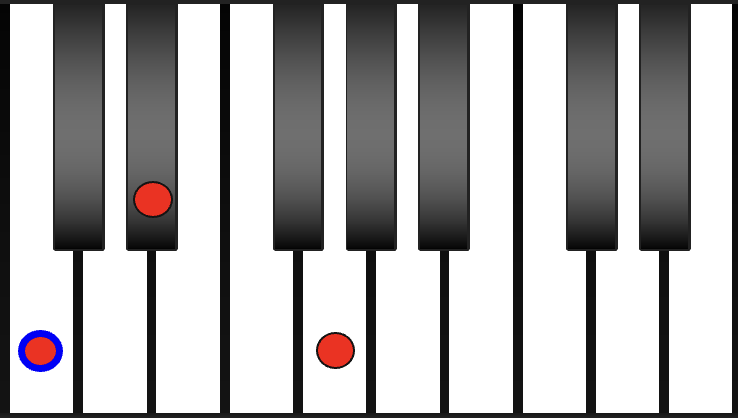

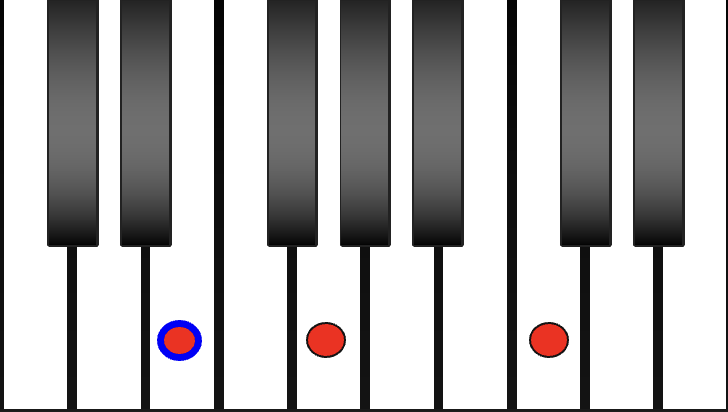

Key Signature - dictated by the notes of a chord. For example, every C-major chord uses the notes C, E, and G.

Tonality - determines major or minor version of the chord. Sometimes, you can determine this easily by guessing whether the chord sounds happy or sad.

Inversion - alters the order of the notes played. In other words, your base note changes.

With 12 key signatures, 2 tonalities, and 3 inversions, this makes this a 72-label problem! Both trained musicians and AI models can struggle to accurately predict them when there are 72 different chords to choose from.

Data Source, Cleaning, and Up-Noising

The dataset used in this project was sourced from the publicly available JazzNet GitHub repository, which contains isolated piano chord recordings designed for music-information-retrieval research. From this collection, 510 three-second WAV files were selected, representing all major and minor triads across multiple key signatures, inversions, and pitch ranges. Because the recordings were already clean and consistently formatted, minimal preprocessing was required beyond standardizing the audio pipeline. Each file was loaded using Python’s librosa library, resampled to a consistent sampling rate, and converted into numerical waveform arrays suitable for harmonic feature extraction. A key limitation of the dataset, however, is its invariance: each chord appears only once and is likely rendered from a virtual piano, raising concerns about generalizability to real-world audio.

To address the limited variability of the original recordings, each chord was augmented with multiple noise-altered versions using white, pink, and brown noise, increasing the dataset from 510 to 2,040 samples. This augmentation strategy encourages the model to focus on chord-relevant harmonic structure rather than recording-specific artifacts, improving robustness to noisier and more realistic audio conditions.

White Noise - broad spread of low-to-high frequencies (loud noise warning)

Pink Noise - louder low-frequency sounds and softer high-frequency sounds

Brown Noise - deepest and lowest frequency, no high-frequency sounds

For more on colored noise, see this article.

Exploratory Data Analysis

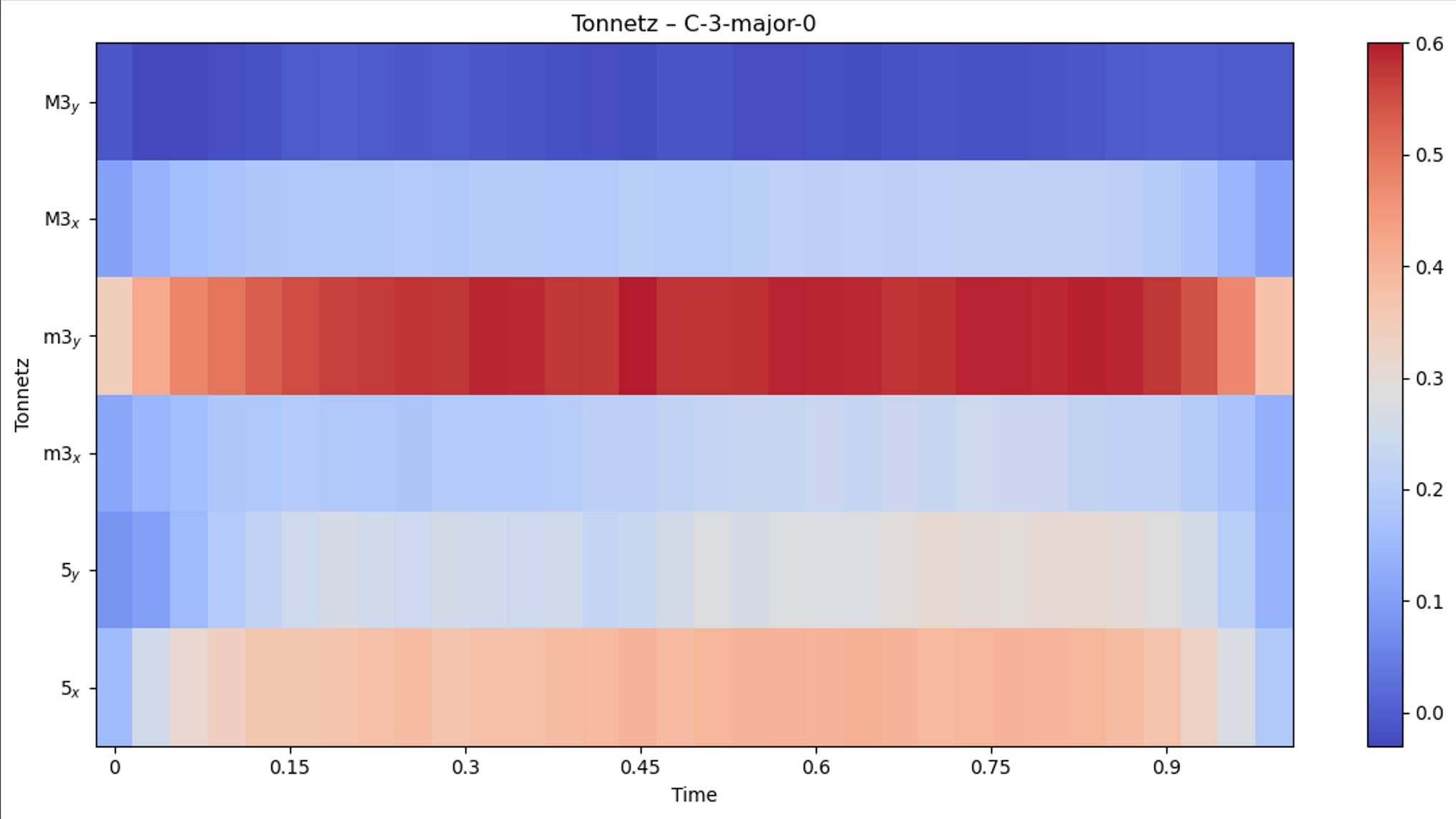

To capture musically meaningful structure, three complementary harmonic feature representations were extracted using librosa: Constant-Q Transforms (CQT), chromagrams, and Tonnetz embeddings.

- Tonnetz features encode tonal relationships between pitches based on interval structure, emphasizing harmonic distance and making them well-suited for distinguishing chord quality.

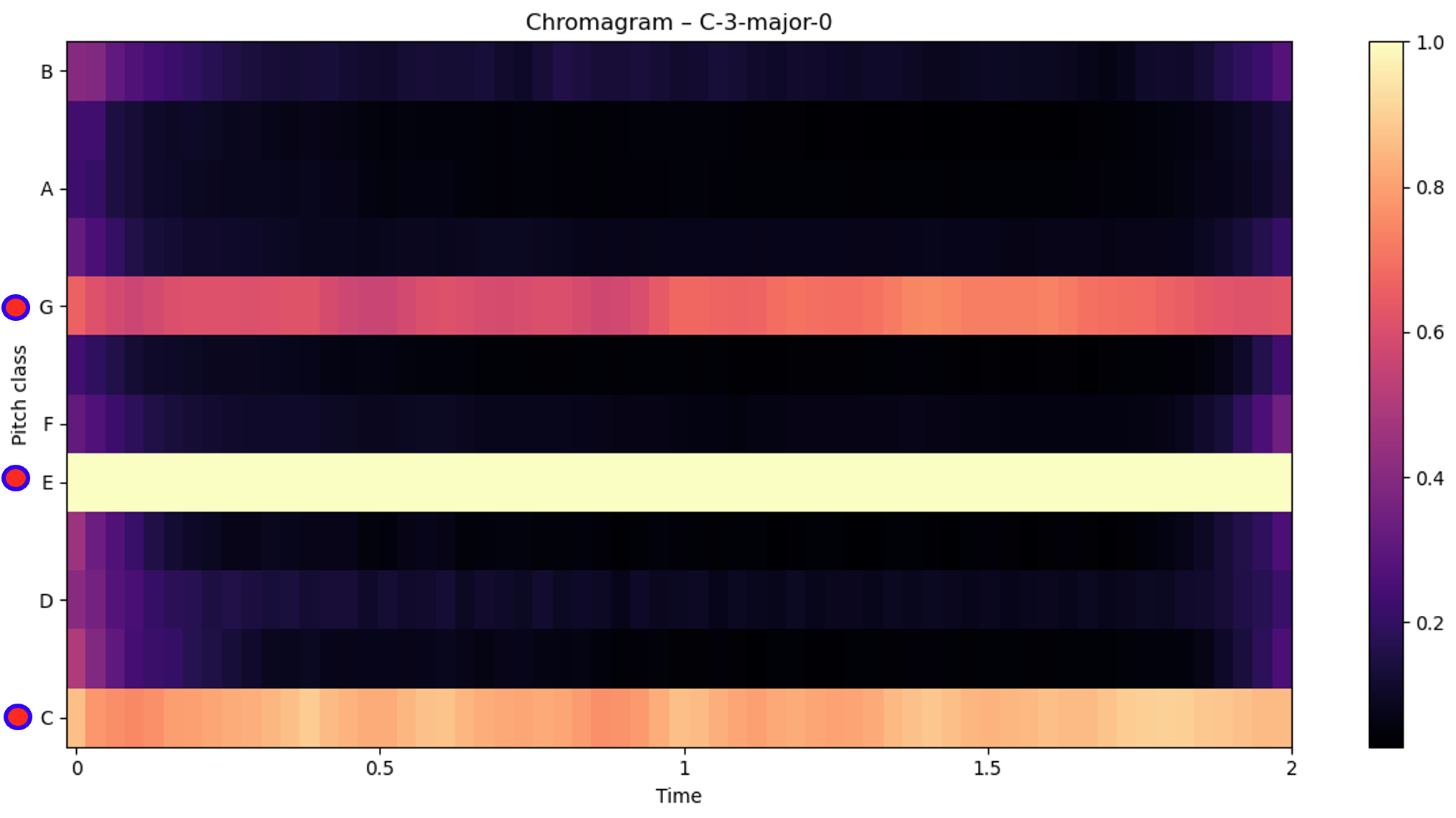

- Chromagrams collapse spectral information into 12 pitch-class bins independent of octave, providing strong cues for detecting key signatures and major/minor tonality.

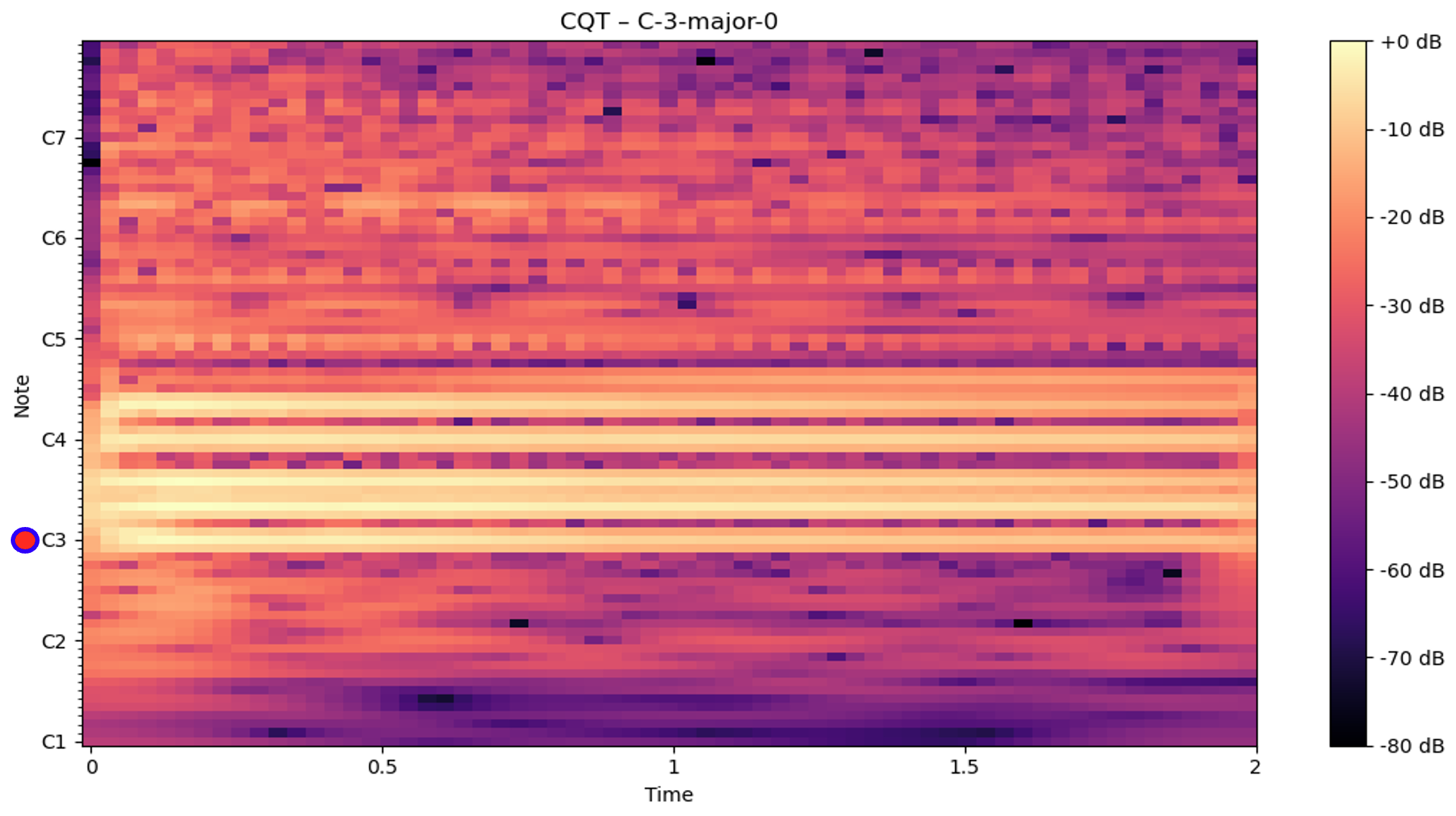

- CQTs represent frequency content on a logarithmic scale aligned with musical pitch classes, making them particularly effective for identifying the lowest pitch present and therefore the chord inversion. This audio-data transformation induces a little more noise than the other transformations, making detection of the inversion more ambiguous than the other clear-cut transformations.

Methods

Classifying all 72 possible chord variants with a single model proved ineffective due to overlapping spectral features and inconsistent inversion cues. In particular, inversion information is often subtle in audio data and far less essential in chord construction than tonality or key signature. A single multi-class model risks misclassifying all components of a chord when only one feature (typically inversion) was ambiguous. To address this, we decomposed the model into three simpler, more stable problems:

-

ToneNet: Predicts Tonality (major/minor)

-

KeyNet: Predicts Key signature (12 classes)

-

InversionNet: Predicts Inversion (root, first, second)

This modular approach reduced model complexity, improved training stability, and aligned with the structure of our input features. ToneNet ingests Tonnetz embeddings, KeyNet operates on chromagrams, and InversionNet uses Constant-Q Transforms. All three networks share a common architecture: 2–3 convolutional layers with ReLU activation, max-pooling layers to reduce dimensionality with each layer, a final softmax output layer, and various regularization parameters (trained uniquely). Convolutional networks were chosen because our inputs are naturally structured as 2D time-frequency matrices, making CNNs well-suited for extracting localized harmonic patterns.

Regularization was used to reduce overfit, particularly for InversionNet, which encountered instability issues when too many parameters were fit. Model performance was evaluated using accuracy. Predictions were interpreted with the softmax probabilities from the final layer as a measure of confidence, allowing us to quantify uncertainty across different chord qualities, pitch ranges, and potential sources of noise. This confidence analysis provided insight not only into model correctness but also into how reliably the three neural networks interpret the harmonic structures of each chord.

Results

All variants of the audio transformations (tonnetz, CQTs, chromagrams) were tested on ToneNet, KeyNet, and InversionNet with a variety of regularization parameters (dropout, learning rate, weight decay). Comparisons between models are found in the appendix, but this section focuses only on reporting the top model performances.

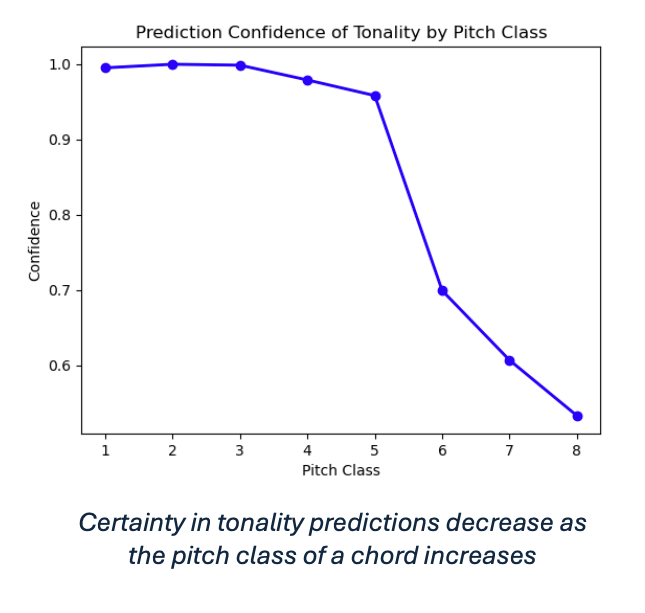

Pitch Class Profiles and Uncertainty: Softmax outputs revealed a clear pattern: prediction certainty decreases sharply as pitch increases, especially for high-register chords where harmonic structure becomes harder to distinguish (even for humans). This diagnostic motivated the training to filter pitches, which substantially boosted model performance.

Predicting Tonality, Key Signature, and Inversion: Removing high-pitch samples (C6 and above) dramatically improved accuracy for all deep learning models. The final results were

-

ToneNet (tonnetz features): ~ 99.7% accuracy/F1

-

KeyNet (chromagrams): ~ 100% accuracy/F1

-

InversionNet (CQTs): ~ 94.3% accuracy/F1

When predicting all chords sampled by JazzNet, the ensemble achieved 94% exact chord accuracy, with the error driven mainly by InversionNet. Tonality and key were nearly perfect (99.3% and 100%).

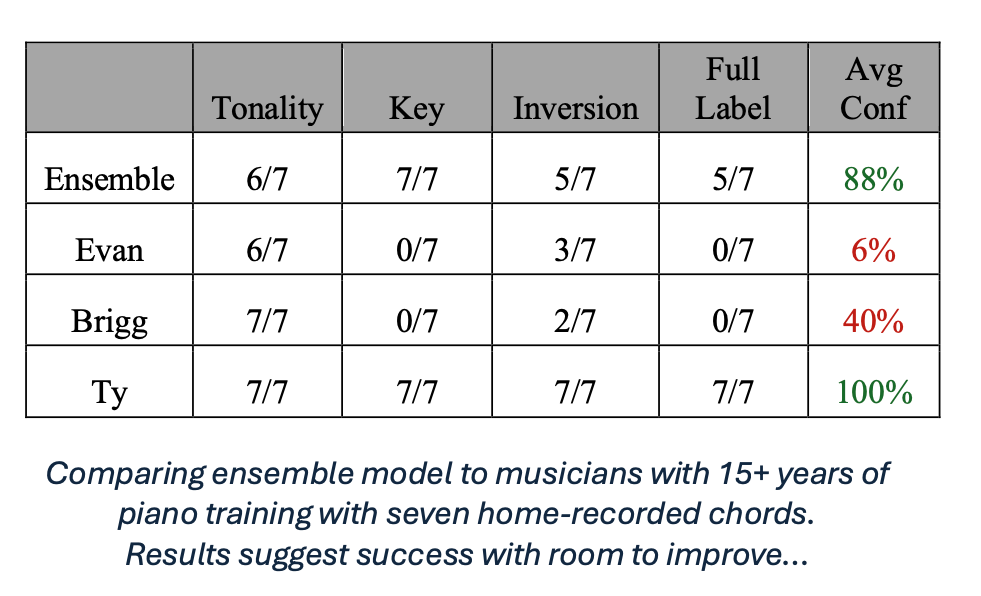

External Validation Exercise with Trained Musicians: To determine how the ensemble network does at (1) predicting chords from new audio sources, and (2) if it can do better than the average musician, I asked three friends who have 15+ years of experience in piano to see how accurately they can classify seven chords I played and recorded on a piano in my home. Below is a table that summarizes the results of this exercise. All subjects predicted tonality almost perfectly. The key signature and inversion were very difficult to predict for Evan and Brigg, which the model clearly does better with. However, Ty has absolute (perfect) pitch and predicted each chord with 100% confidence, completely outshining the ensemble.

Conclusion

From our research here, we have determined that

-

AI can accurately classify a chord

-

AI can classify better than the average musician

-

AI may not perform as well as a musician with perfect/absolute pitch

Another key aspect I learned from this project is that the most powerful neural network, whether it has transformers, convolutions, or deep layers with fancy activation functions, nothing will be better than the right data transformation. What made the deep learning model accurate was the extracted and clear signals from librosa and the CQTs, chromagrams, and tonnetz. Evidently, because of how clear the signal was, an ensemble deep learning model may not even be needed: some combination of logistic regressions (or perhaps multivariate) could do just as well and take less time to train. Decisions can also be made by humans in making their guesses on the key signature, tonality, and inversion just by looking at these features. Regardless, the deep learning propels concepts in automatic detection, and shows significant potential.

Future work could expand to consider identifying additional types of musical features: seventh chords, diminished chords, augmented chords, arpeggios, scales, progressions, and other multi-note combinations, all could be classified. This type of automation can additionally expand to train AI to crawl through music, learning the patterns, motifs, and other components that create the genetic makeup of a song. Overall, I had a blast on this project, and I express my gratitude from my deep learning professor and the JazzNet GitHub Repository for making this work possible.